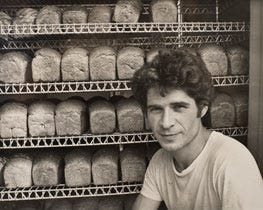

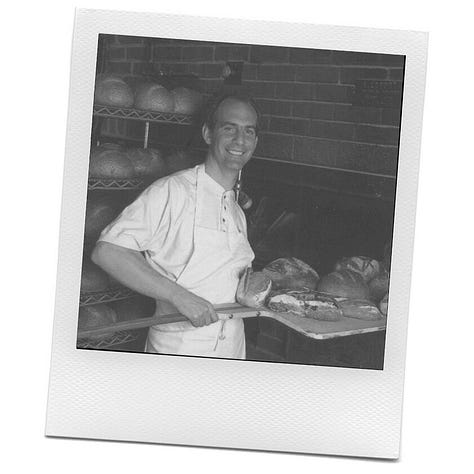

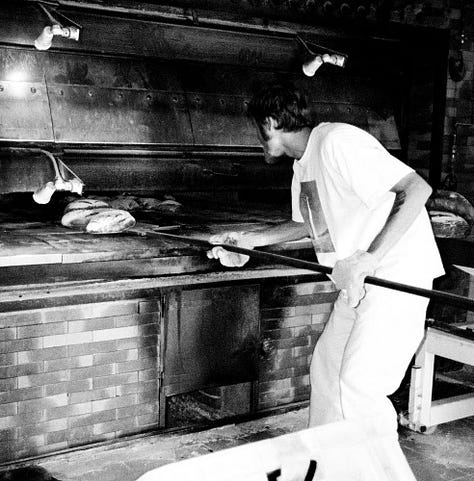

What is ‘country’ bread: what country is it from, and what sort of bread is it? In 2024 at least, the answer is complicated. Complicated, and also an interesting conversation. As I mentioned in the intro to this journal, most of what I write here will be ongoing discussions - especially when the answer is layered with decades and centuries of tradition, culture shaped by diverse regional agriculture and preferences. The basic idea is simple, but evolution in style, ingredients, techniques, consumption, and general use at home and in restaurants has been steady. In the late 1970s and early 1980s I was a kid, but during this time a handful of dedicated American bakers had traveled abroad and tasted Pain de Campangne in France were smitten. Of course every country in Europe east and west had their own distinct style of these breads some similar, and some radically different. But, in that era French bread was held in the highest regard by not only America, but also much of Europe. Claus Meyer, co founder of Noma and creator of the Nordic manifesto was inspired by his time cooking in France: the seasonality, local focus - and how powerful that direct translation shaped the culture of society. Food shaped everything. Americans had started to enjoy imported soft ripened cheese and wine slowly became a frequent accompaniment enjoyed with dinner. With wine and cheese came bread. Americans were already accustomed to dry flavorless white bread available in various forms, but Country bread was not yet a thing here. What I consider the first generation of artisan American bakers to bring these traditions to us were Dan Leader (Bread Alone) in upstate NY and Steve Sullivan (Acme) in Norhern California followed during those few golden bread years in the 80s by Nancy Silverton (La Brea) in Los Angeles, and Richard Bourdon (Berkshire Mountain) in Western Massachusets. While Dan and Steve seemed initially French focused, Nancy brought some Italian style into the fold. Bourdon had already been living and baking in Europe, and he brought a unique perspective from more esoteric baking fringes (vs. France) working with fresh milled flours used to make biodynamic whole grain breads. Each of these pioneers added their own new American regional style, but they were all dedicated to learning and bringing the tradition of what we now call country style bread to the US which elevated and pushed our aspiring bread game into a competitive position.

The simple idea is a bread - not too white, not too whole wheat, but somewhere in between. Maybe, or maybe not including a portion of rye flour as rye was less expensive than wheat and grew well in more inclement climates. In theory, Country bread was affordable and accessible. Baked on a hearth - ‘free form’ vs. in a pan (like sliced bread). Baking free form on the hearth gives the bread a substantial crust. In theory anyways: to this day, there are lots of country breads in America that are soft as nerf balls, but that’s ok; just different from the 80s era influence when we were trying to elevate our bread game from flavorless soft sliced white loaves to something with more character and better suited to Euro style dining becoming popular on the coasts.

The type of flour used along with natural leavening (levain in French) were the first departures from the industrial commodity bread we were used to eating. In the European countryside, mills were traditionally circular horizontally rotating pulverizing stones powered by water (near streams or rivers) or windmills. These early style mills typically didn’t produce super refined flours, but rather whole grain or high extractions (just partially sifted removing the coarsest 10/15% of the bran utilized to feed animals on the farm. Refining the flour further to 45/50 % extraction would give you a very fine white flour - delicate and supple, but also lacking fiber, nutrients, and flavor. More importantly from a business perspective: this super refined flour was too expensive for true country bread which was a staple of the working (wo)mans diet. In the late 1700s early 1800s French workers consumed 1-2 pounds of bread per day, contrasted with just a few ounces on average today. This was serious bread, used not only to fill the belly but also to soak up every last bit of sauce and juice and whatever sustenance remained in the bowl or on the plate.

For many of us, the first authentic French country bread we encountered was Pain Poilane - the bread of Paris baker Lionel Poilane. By far the most famous French bread outside of France, Poilane was shipping thousands of frozen loaves to the US in the early 1990s in the form of a giant round boule of a loaf. With a dark, thick crust the color of burnished mahogany, caked with a layer of flour the loaf had risen for several hours in baskets lined with Belgian linen so as not to stick. Poilane bread is made with a proprietary blend of stone milled French wheat and naturally leavened. It is le vrai Pain au Levain cuit au feu de bois - veritably baked in a wood fired oven. In France there are strict rules governing these details plus how and when your bread can be labeled as such. Famously, Poilane has never made baguettes, which he noted were a recent bread creation, and certainly not the bread that France was built on. Around the time that these American bakers were beginning the artisan bread movement in the US, France too began to look back. As if the American infatuation with French Pain au Levain had caused the French to reconsider the mastery they had started to leave behind with the advent of industrialization. Traditional country farmhouse loaves, keeping moist for several days due to the long natural fermentation, soon became sought after by sophisticated bohemian gourmands. Or as they say: the city folk wanted country bread, just as the country folk wanted delicate baguettes from the city.

I had heard of Pain Poilane by the time I was apprenticing with Richard Bourdon, but I hadn’t made it to France yet. Richard was using organic stone ground flour from Lindley Mills in North Carolina and he had a thing about dough hydration. He fervently believed that wheat bread dough needed to be properly hydrated during fermentation so that when it was baked there was enough hydration to properly gel the starch (fully cook) so it would be more digestible. Higher hydration and fully baking the bread to internal temperature of 210+ F after a long slow natural fermentation made for a much healthier loaf from the perspective of digestion and nutrient assimilation. I grew up eating brown rice and working in health food stores as a teen, so he was speaking my language.

It seems endearingly quaint now when I remember another thing that Richard taught me about mixing higher hydration doughs as an apprentice: it was literally job security. In lots of ways Richard was extremely efficient - he liked to do things deliberately. The goal was to minimize daily maintenance like cleaning and organizing. Mostly because he ended up doing a lot of this daily upkeep himself. Reliable workers were scarce and seasonal in the small town along the Housatonic River. But high hydration bread dough was challenging, messy, and non- negotiable. At first the dough seemed impossible to work with- like shaping pancake batter. Richard mused that no machine could ever handle the complex dance it takes to maneuver such wet doughs into a final loaf of handsome country bread. That was 1992.

Of course, bread making technology has evolved since then; and I started a journey in the early 2010s to research equipment as I was preparing to scale production. I visited factories in Italy, Germany, and Japan. Not so much France at the time as my own doughs had continued down the path of Bourdon with gradually increasing hydration, longer fermentation times, while incorporating more whole grains and fresh milled inclusions. Italy had engineered certain machines to handle ciabatta and panettone doughs - about as wet and sticky as it gets. Germany had machines to manage viscous, gluey rye doughs with huge sourdough productions. And Japan had built a machine to wrap glutinous rice mochi around ice cream balls- no breezy feat. At the time, super high hydration doughs were considered defective at best in France, and scandalous at worst: a holdover from more ancient bread times when ‘selling water’ by stretching your dough with more hydration veered into nefarious territory.

Thirty plus years in, I can say Richard’s gentle hubris has mostly held its ground. Though still quite challenging to work with wet doughs, there are some machines now that can help streamline the process a bit. But until you reach a certain level of scale- it’s quicker and more efficient to do the handwork as it may actually take more time to disassemble, clean, and reassemble the equipment that is supposed to be making your job easier. Like under a thousand loaves per day hands are faster, over 2000 - machine starts to make sense. The in-between space which is different for every situation is the crazy making zone: you don’t want to linger there for too long. I remember having the very strong conviction of an impressionable 20 year old that becoming a skilled maker of true artisanal bread - something that could only be made by hand- was a noble endeavor and yes, with a measure of job security sounded like a bonus.

Artisanal as a bread descriptor, was not so commonly used in the early 90s. Same goes for ‘rustic’ and ‘country’. On days when the bread didn’t quite meet my standards (impossibly high always even if I wasn’t quite sure where I was supposed to be landing), Richard attempting to assuage would say ‘it’s all good man, people love rustic bread’ That drove me nuts. To this day, I strive only to achieve rustic bread when that’s precisely what I’m aiming to make as purely aesthetic adjective. I googled rustic bread and the internet told me (mind blown) that it refers to high hydration doughs. Country bread remains synonymous with that first French loaf I described, but also in my belief includes many more blends of diverse grains in more countries now than ever in the past (relevant exploration found in Tartine Book 3).

So what do I know, except that things have come full circle maybe several times by now and certainly still evolving. Thankfully for the sliced bread lovers (myself included some days) one can now find sliced crusty country style loaves - even thinly sliced quarters of Poilane’s famous boules - alongside soft sliced bread in bags with a layer of flour on top lending a sort of faux country aesthetic to the ultimate convenience of modern bread culture. More importantly now than ever, is not what or how we label bread, but what and how we actually make it- with what intention.

This rambling is just a warm up thought (and memory) exercise on the consideration of Country bread then, and now. We haven’t even touched on the nature of country bread crumb: is it expansive with uniformly open holes (selling air along with water now) vexing the poor jam spreaders; or is it heavy and dense spiced with mountain herbs? We will get into all of that, in what I hope will be an illuminating and infinite conversation. I’ll be making some new bread over the next few days with intention; and look forward to sharing where this path is headed.

love this mate.

Absolutely interesting thoughts and insight. Thank you for sharing!